Why taxpayers are the biggest loser in the debt ceiling deal

The good news (if you might even call it that) is that President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy reached a deal to prevent a default. The bad news is that the deal does nothing to address growing spending — the culprit to our debt crisis. Instead, the deal mostly includes symbolic spending cuts that won’t matter in the face of the blank cheque that McCarthy has agreed to give to the Democrats.

Imagine, if you will, a household that has over $300,000 in credit card debt, earns $50,000 a year, but spends at least $70,000 in the same period, adding over $20,000 to its credit card debt every year. Furthermore, imagine that the household’s spending is expected to grow at a higher rate than income. Everyone would agree that the sensible thing for such a household to do would be to cut spending or at the very least limit its growth, while gradually cutting debt to align spending with income. It would be illogical for that household to get new credit cards and keep on with its spending spree.

Yet that’s what President Joe Biden and McCarthy have agreed to do in their debt ceiling deal.

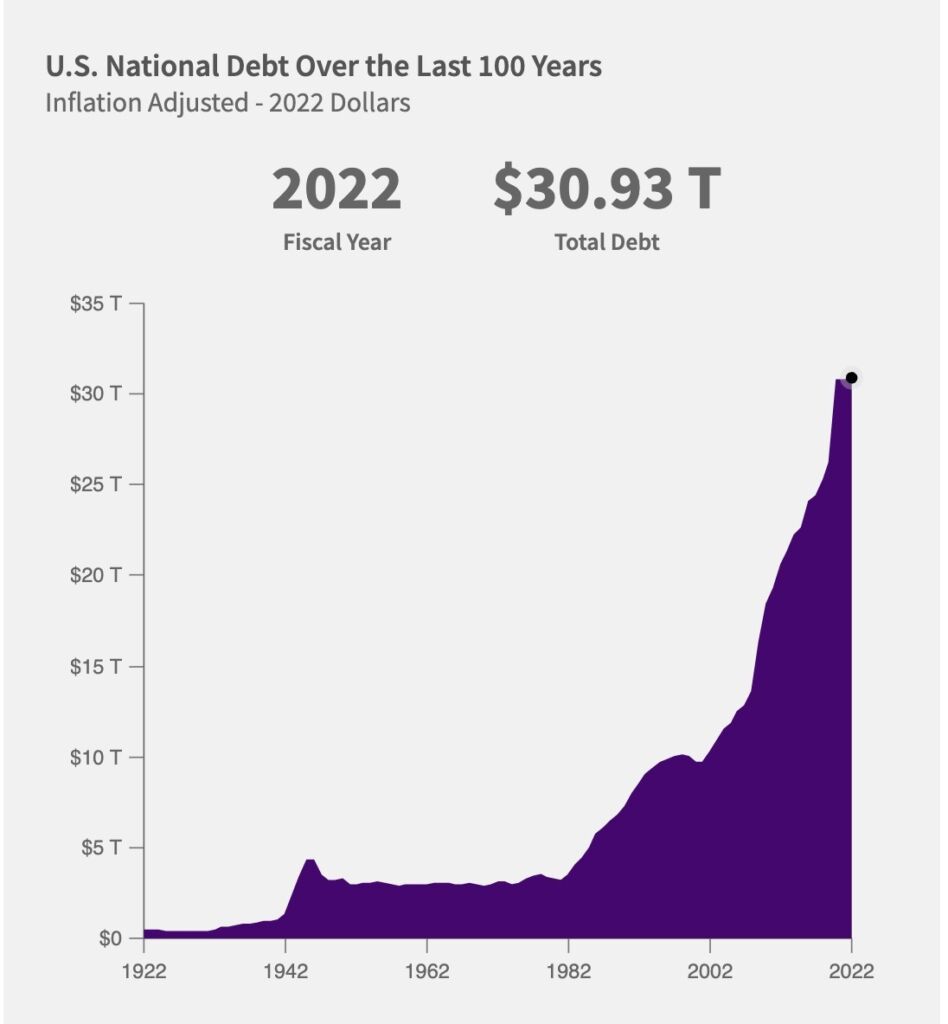

Except for the period between 1998 and 2001, the United States federal government has run deficits every single year since 1970. With the national debt at about $31 trillion, and over 100 percent of GDP, the US is one of the most indebted countries in the world. Not to mention that debt is expected to grow significantly in the coming decades, thanks to growing Medicare and Social Security obligations.

But in their new deal, Biden and McCarthy have agreed to suspend the debt limit for the next two years, giving legislators a blank check without doing anything substantial to curtail spending. Sure, from the very beginning, debt ceiling talks have not including Medicare and Social Security, so it was unlikely that any deal would have touched these programs — which in itself is a problem.

But even the spending restraints that are currently in the deal are nowhere near what Republicans asked for in the Limit, Save, Grow Act. In fact, when the Act passed it called for, among other things, a suspension of:

the debt ceiling through either March 31, 2024 or a $1.5 trillion increase from the current $31.4 trillion ceiling – whichever comes first.

As well as:

return total discretionary spending to the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 level in FY 2024 and cap annual growth at 1 percent for a decade thereafter

In the debt ceiling deal, however, only non-defense discretionary spending is touched — but only until 2025. After that, there are no spending caps, only “non-binding appropriations targets.”

The CBO estimates that the debt ceiling deal will reduce deficits by $1.5 trillion over the next decade — which is significantly lower than the $4.8 trillion in savings that were projected for the Limit, Save, Grow Act. And assuming Congress does not honor the proposed non-binding appropriation targets after 2025, the savings would be even lower. Meanwhile, the debt ceiling will be suspended until January 1, 2025 — about nine months longer than what was passed in the Limit, Save, Grow Act

Who won?

For people thinking along party lines, there is something in the deal for everyone, likely due to the concessions that each party has had to make.

There is, however, one clear loser in this deal, and it’s neither Democrats nor Republicans, but taxpayers. If Congress passes this deal without addressing growing spending — and consequently growing debt — it will potentially put taxpayers on the hook for higher taxes in the future. High and growing levels of government spending and debt, moreover, lead to economic stagnation or decline, as I have previously outlined, hurting taxpayers (and the rest of the country) even further.